The Life and Adventures of Colonel Tim Sweeny, RAPC

A quick note to the reader: all place names that are used are the original names used by Col Sweeny in his memoir. The modern locations and place names have been included when each location is first mentioned.

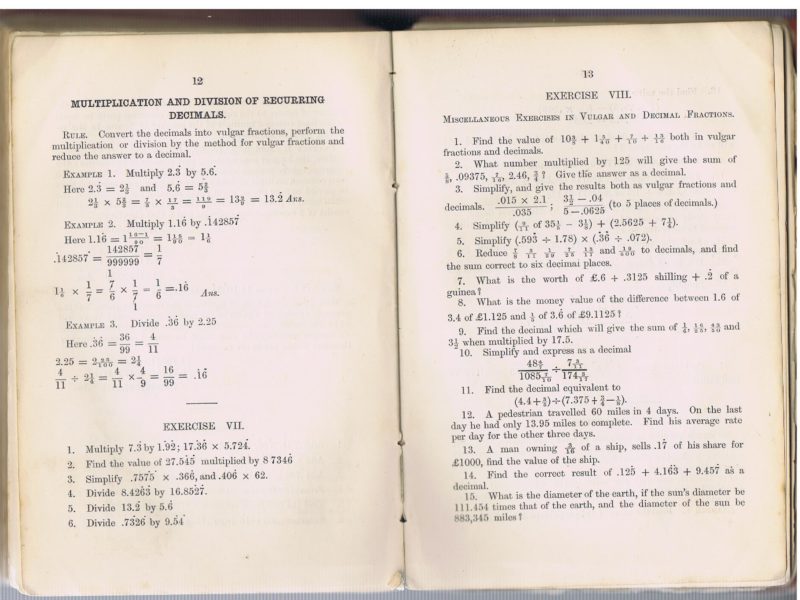

Born in 1898, Colonel Thurston Humphrey ‘Tim’ Sweeny first joined the army as a second lieutenant of the Royal Engineers. Appointed in September 1917, he served on the Western Front attached to the Guards Division, where he was severely wounded by shellfire in August 1918. He returned to active service and in March 1919 was promoted to lieutenant. He served his post-war service with the Royal Engineers in Jamaica, following this with a degree course in engineering at Cambridge. After completing his degree and before returning to Jamaica, Sweeny commanded an engineer unit at Chatham. In September 1928, he was promoted to captain, and a year later was married. Sweeny’s increasing deafness contributed to his decision to transfer from the Royal Engineers to the RAPC in April 1933. The following ten years resulted in Sweeny serving in numerous countries including Egypt, Palestine, Cyprus, India, French Indochina (Vietnam), Singapore, and Batavia (Jakarta, Indonesia), and received a number of promotions. His service in the Far East was, at times, unusual, and his success in completing several complex operations was awarded an OBE.

French Indochina (Vietnam)

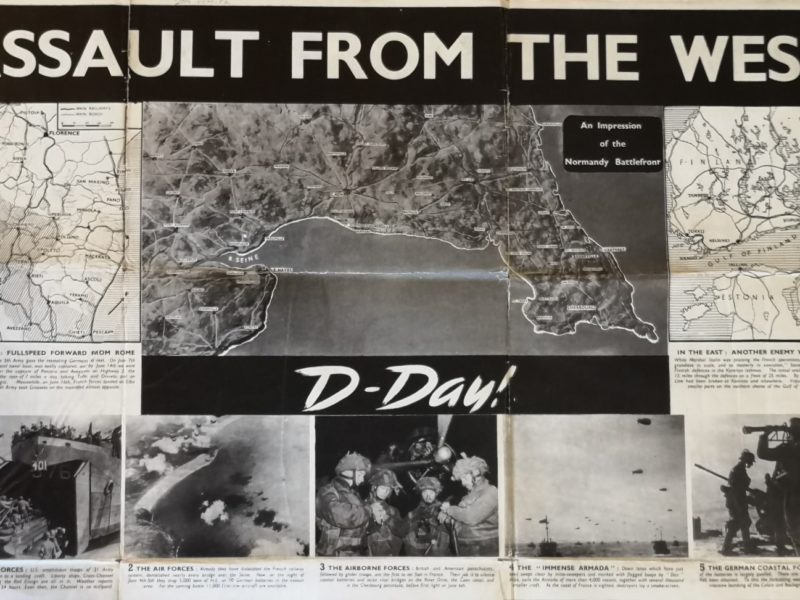

Towards the end of August 1945, (the now) Major Sweeny was ordered to join the No.1 Commission as a Financial Advisor, being aided by an RAPC captain and two experienced NCOs. Little was initially known of the commission’s functions, and Sweeny and his team spent several weeks in India purchasing food and weapons whilst awaiting further instructions.

Leaving a week late, Sweeny finally arrived on their three-day layover in Rangoon (Yangon), and without any definitive orders, met the senior RAPC officer where he was repeatedly told to ‘advise the Commission on financial matters and take responsibility for the RAPC Army Cash Offices.’ The following day, he flew out with the 7th Machine Gun Jats, heading for Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City). Upon the plane landing, Sweeny drove his own jeep, and was amazed to find that his team were to be guarded by armed Japanese soldiers. Recent enemies were now his bodyguards.

Welcome to Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City)

Sweeny reported to Major General Sir Douglas Gracey at his Palais Jucoch headquarters upon his arrival in the city. As in Rangoon, he was ordered to handle all financial matters, receiving the title of Financial Advisor Saigon.

Six weeks after his arrival, Sweeny and his small team, along with a platoon of Gurkhas, visited the Yokohama Specie Bank (the pre-war HSB Bank), as this was the main financial link between Saigon and Tokyo. Upon arriving, they found a building the size of the Bank of England which was staffed by hundreds of Japanese clerks. Seizing control of the building, Sweeny ordered the Gurkhas to search every clerk, and to collect and label every key. The two chief cashiers were retained and showed Sweeny where each key fitted. Though they complied, an issue arose when it came to the second door of the strong room. The two combination locks had been jammed and neither the manager nor his clerks could open the door, ‘not even with the assistance of the occasional prod in the back with a kukri’.

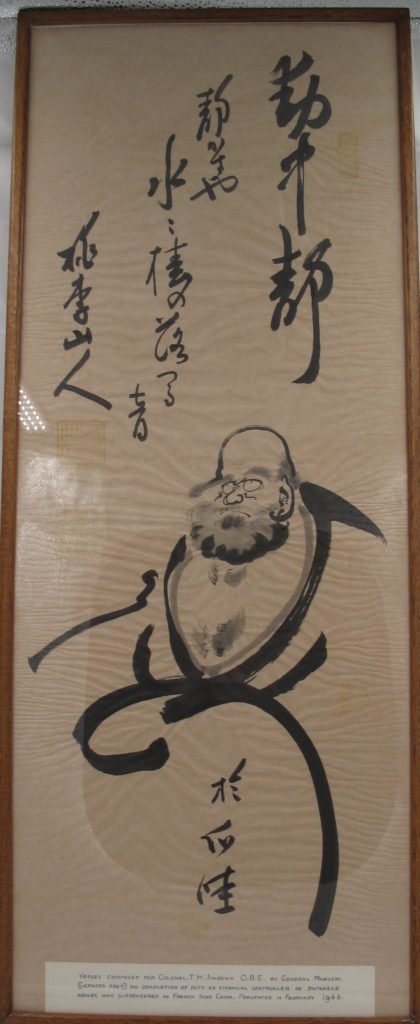

Sweeny gave the manager 24 hours to open the door or threatened to hand him over to the Military Provost Staff Corps, to be tried as a war criminal. The manager returned within an hour with a Chinese locksmith who had the door open within twenty minutes, holding 27 million Piastres. This was the equivalent of around £113,000 in today’s money. The seizure of the Yokohama Specie Bank was a major success for Sweeny, providing access to a financial reserve and offices. A week later he was appointed Custodian of Enemy Booty on behalf of the Victorious Allies.

The Hunt for the Missing Millions

Following the seizure, Sweeny’s investigations revealed that Japanese forces had removed a colossal sum of 615 million Piastres (around £2.6 million in today’s money) from banks across French Indochina just before the arrival of British troops. Initial requests for the Japanese Army to hand over their military accounts were met with responses that the money had been accidentally incinerated. Sweeny was not convinced, and informed Gracey that the 615 million Piastres would support an armed insurgency 200,000 nationalists for a considerable period. Sweeny then dictated a precisely worded signal to Field Marshal Terauchi on behalf of Gracey, ordering Terauchi to provide an explanation for the discrepancies, noting that lost information or incinerated records would not be accepted as an excuse.

Within an hour, General Mabushi visited Gracey, asking what the retribution for keeping this missing money might be. Sweeny implied that no Japanese officer or soldier would be permitted to leave French Indochina until answers were found. Two hours later, two tons of accounts were delivered to the bank, lining the walls of Sweeny’s office. It would take him three months to work through it all, with the assistance of two Japanese Account Officers.

The search resulted in the discovery of occupation currency being printed for Siam (Thailand) Bhats and Indian Rupees in a nationalist stronghold. Sweeny identified the location from the bank documents and an operation was organised to destroy the plates and presses, bringing back the specialist paper to Saigon. The operation was another success for Sweeny.

The Englishman’s Gold

During a meeting with three Japanese colonels from the Japanese Finance Corps, it was revealed that they were holding £2.5 million (just over £85 million in today’s money) of gold on behalf of an English national. Although he had fled French Indochina for Australia, he had arranged for all the proceeds to be paid in gold, which were retained by the Japanese. Upon his return to Saigon to collect the gold, he found that Sweeny has confiscated it and refused to return it, implying that collaborators should be hung. No-one in the No. 1 Commission seemed keen to prosecute the individual and so he was released but the gold was never returned.

The Indian National Army

The Indian National Army was a military force of Indian nationals, selected by the Japanese from Allied Prisoners of War to act in India. The force was led by former Colonel Chaterjee, who had been promoted to Major General by the Japanese and who served on Field Marshal Teraugi’s staff in Saigon.

A chance conversation between Sweeny and the Chief Intelligence Officer over dinner revealed that Chaterjee was wanted by them, but that the trail had gone cold. Sweeny recalled an unusual entry in the INA accounts: a bankers draft for 3,200 million Piastres (£807,707 in today’s money) had been issued to Chaterjee, which was yet to be cashed. Since the only bank capable of cashing the draft lay in Hanoi, it would be the obvious place for Chaterjee to head, despite the potential 800-mile trek on foot. Following Sweeny’s advice, intelligence officers capable of recognising Chaterjee were flown to Hanoi and waited outside the bank. The following day, Chaterjee was successfully apprehended whilst walking into the bank, and was returned to Saigon.

Charterjee was charged with war crimes and sent to Changi Prison in Hong Kong. Later, he was collected by two British officials and flown to India, where he was allowed to disappear. The success of this operation highlighted the importance of collaboration and sharing information between the financial and intelligence elements of the No. I Commission, and added another success story to Sweeny’s record.

The Beauty Parlour Network

A few days after Chaterjee’s arrest, Major Sweeny received information from intelligence that it suspected a ladies beauty parlour on Rue Catinet (Bond Street), in Saigon, was issuing funds to insurgents. He ordered for the shop be closed, the staff and manager be separated, and the safe keys and account books be removed and brought to him. It took Sweeny several hours, but he discovered a financial network distributing cash to shops in various towns. Each of these shops were closed and the accounts examined, revealing another network distributing cash around French Indochina. Although over 200 million Piastres (£837,197.00 in today’s money) had already been distributed, a major source of funding for the insurgency had been closed off.

The Raid on the Qui Nhan Bank

In November 1945 a dishevelled Frenchman came to see Sweeny. He was the manager of a branch of the Bank of Indochina, in the provincial centre of Qui Nhan (Quy Nhon). Although there were 500 Japanese soldiers stationed there, a force of 10,000 nationalists were using the town as their headquarters. The nationalists had seized the bank and were using the contents of one of the vaults to pay themselves. The manager, although removed from the bank, had maintained the keys to the second vault and walked to Saigon. Located within the vault was 20 million Piastres (around £83,700 in today’s money). Sweeny asked the manager to sketch the town plan; the bank lay at the end of the town square, flanked by warehouses and approached by a single road. A joint Army and RAF conference formulated a daring plan. The Japanese commander was ordered back to Saigon and briefed on his role.

An RAF Dakota began making flights over the town. Initially insurgents responded with fire but by the fourth day, no longer bothered. On the fifth day the aircraft circled, the Japanese forces blocked off all the entrances to the square. When secure, the aircraft landed and taxied into the square near the bank and turned around, leaving the engines running. The road was twelve inches wider than the wheels.

The bank manager jumped out along with an unnamed army officer and entered the bank, opened the second vault and started to bag up the highest value notes. Anything less than 100 Piastres was left behind. Once the nationalists realised what was happening, they attempted to enter the square but were beaten back by the Japanese. Once satisfied that they had all the funds they could carry, the bank manager and officer boarded the plane which accelerated down the road and quickly took flight. The whole event had only taken fifteen minutes and was a resounding a success with 19 million Piastres recovered (£79,500 in today’s money).

With the cessation of pay for the nationalists the insurgency petered out for around thirty miles around the town. Sweeny remarked that the ‘lack of cash can often be more of an inhibition to insurgency than bullets and bayonets.’

RAWPI

Repatriation of Allied Prisoners of War and Internees was a key element of the surrender of Japan, and Japanese forces were required to identify camps and protect and provide support to their former prisoners. As Sweeny developed his ‘money map’ – locations where large sums of money had been directed by the Japanese – he noticed that 12 million Piastres (just over £50,000 in today’s money) had been directed to a location near Hue, a coastal town 400 miles north-east of Saigon. At ‘morning prayers’, he posed a general question to the present branch commanders. With nothing forthcoming, the naval liaison sent a cruiser in the area to investigate. A shore party quickly found an unreported prisoner of war camp holding 500 senior officers believed to be an insurance policy against the mass execution of Japanese soldiers. The prisoners were rescued and this marked another human success story for Sweeny and his team.

Bon Voyage

Eventually, French forces were able to organise sufficient numbers to take responsibility for security in French Indochina, and No. 1 Commission planned its withdrawal. At a cocktail party held a week before departure, Sweeny was asked by the French General Leclerc what would happen to the booty in the bank. He replied that the cash would be handed over to the French Finance Department upon agreement that they would supply Malaya with an equivalent amount of rice. The rest of the money would be returned to Singapore. Though nothing more was said on the matter, Sweeny suspected that the French would try to undermine this plan. This was supported by the fact that Sweeny and the money were planned to leave the day after the departure of the majority of British forces.

On the day of departure, Sweeny was awoken an hour early to be told that French soldiers were preventing access to the bank. He asked the 7th MG Jats, who had been allocated to support him and whom he had served with in Saigon, to attend the bank with him an hour later. Upon arrival at the bank, they found French soldiers guarding the entrance. The French NCO in charge explained that he had orders to not allow anyone to approach the bank, particularly Sweeny, who was to be stopped by any means necessary short of death.

Sweeny requested to speak with their officer, who walked with him up the steps of the bank as the French soldiers watched on. The officer continued to repeat his orders to limit access to the bank, not noticing the Jats moving into position. After listening to the French officer’s explanation, Sweeny asked him to turn around, at which point the French soldiers realised they had been surrounded and were now covered by the weapons of the Jats. Sweeny pointed out that it would be a waste for everyone to die obeying orders, and suggested that the French put down their weapons and enjoy some coffee in the adjacent café. Upon getting his way, he gave the French the Piastres he held, whilst the bank vault was emptied onto the British lorries.

After 1947

In 1947, in recognition of his service in the Far East, Temporary Lieutenant Colonel Sweeny was awarded an OBE. Upon his return to Europe, in 1949 he was posted as Staff Paymaster to Headquarters BAOR, before his promotion to Lieutenant Colonel became permanent. A year later, he was posted to the Regimental Pay Office Newcastle as the Regimental Paymaster and promoted to Temporary Colonel. In total, Colonel Sweeny served in the RAPC for 23 years, remembered by many for his eccentric stories from the Far East, and for his keen sporting prowess, representing the corps in sports such as tennis, hockey and golf throughout his career.

Retirement

Tim Sweeny retired from the Army in 1956, settling in Bournemouth and turning to golf and local politics to occupy his time, firstly as a councillor in Lymington and then on the County Council where he chaired the Finance Committee 1962-63, Parks 1963-64 and Sea Defences 1966-68. Sweeny was also a staunch supporter and fundraiser of the ‘Not Forgotten’ Association which assisted disabled servicemen and women. Tragedy came to Tim Sweeny in 1961 with the death of his only son, a Captain in the 7th Light Parachute RHA, during a training exercise in Wales.

Colonel Tim Sweeny died in January 1969. A number of his objects are on display in the museum.